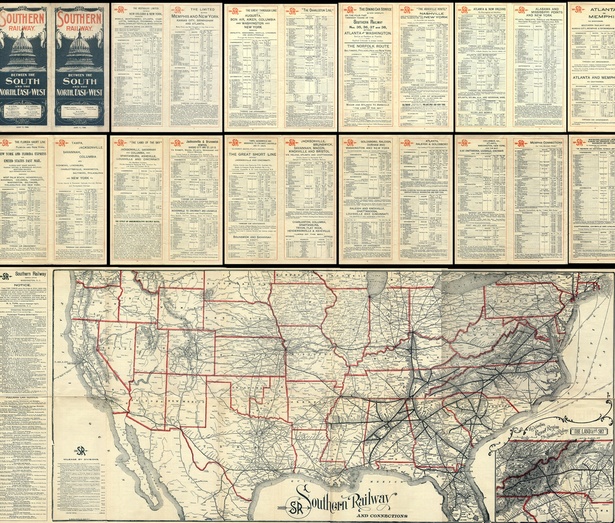

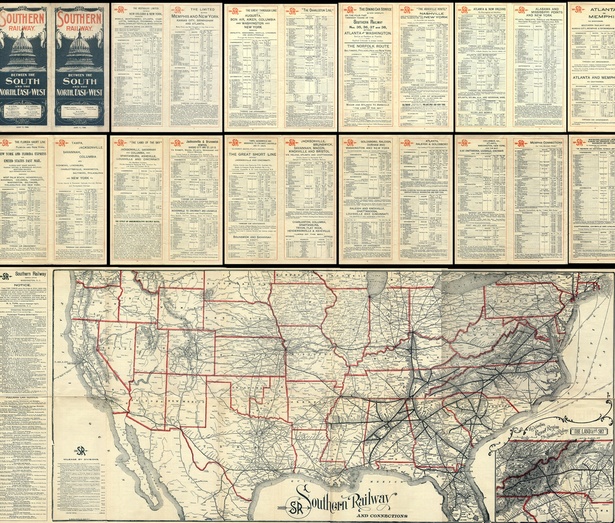

The Lost Excitement, Pathos, and Beauty of the Railroad Timetable

An elegy for the paper symbol of the mechanical age

by

Henry Grabar

It was the lowly timetable that bore testament to the train’s transformative influence on modern life. In the corporeal metaphors that the industrial rail network often inspired, stations were the beating hearts, rail lines the arteries, trains and passengers the vital blood. The schedule might be called the DNA—the hidden, essential set of instructions, part command center and part record book. It’s the same time in New York as in Boston right now, and for that you can thank the timetable. It was once the proud face of the industry. In pamphlets, on posters, in advertisements in papers, railroad companies touted times like competitive runners. Boston to New York in eight hours! Week-long journeys shrank to days, days to hours, the trip across Paris—an easy hour by horse-and-carriage or streetcar—to minutes.

Read this essay at The Atlantic